By Dr Emmi Pikler

An excerpt PEACEFUL BABIES – CONTENTED MOTHERS (published in 1940),

taken from the Sensory Awareness Foundation publication BULLETIN (Number 14/Winter 1994).

Children, particularly in cities, tend to sit poorly and have bad posture. They cannot sit, stand or walk properly, not to mention more complicated movements.

This, of course, is not self-evident to every reader. I can hear the astonished responses: “What? My children can’t move?!” “My little daughter could already sit when she was just four months old” “Mine was already standing at six months”… “When my son was not even one year old, he was walking.”

Children do sit, stand, walk, and move – that is true. But how? … They tire easily. They fall often and clumsily. Quite often they hurt themselves seriously. They do sit, stand, walk etc., but not really….

Of course, we adults are not any better in this respect. We think it is natural that after a one-or-two-hour walk we can’t stand on our feet any longer, that after a few hours of sitting we have difficulty in moving our stiffened limbs. That is not at all natural, however. If one sits correctly, sitting is not tiring. If one stands correctly, standing is possible for much longer than we can imagine….

Or, let us consider animals. They move in a simple way, in harmony with their nature: a deer, a cat, an ape, a buffalo or an elephant. The largest, the most dignified, the slowest, the most unwieldy animal, each one is equally capable of swift and instant movement without losing its innate grace – not like us who when running only ten or twenty steps (for instance to catch a bus) run in a stiff and strained manner and are out of breath for many minutes afterward.

Even the fastest movement an animal makes never seems hurried. And most importantly, the greatest achievements are attained with the least amount of effort.

Why is it that this natural, quiet serenity, the natural simplicity and efficiency of the posture and movement is so often completely lacking in our children? Does it have to be that way?

No.

In the development of movement we are not by nature as different from animals as we generally assume. The wish for our children to move beautifully and according to their innate nature is by no means a far off and unattainable dream. To move correctly is an inborn ability not only of animals but also of human beings, including city people. If we provide enough space and possibilities for moving freely, then the children will move as well as animals: skillfully, simply, securely, naturally.

Don’t misunderstand me. Not every human being can have a perfect figure. I am talking about gestures, movements, carriage. There will always be people with less than harmonious proportions and other small imperfections. However, the imperfections we may be born with do not need to grow progressively worse with time, or make us unable to deal with the average demands for movement in everyday life. Even animals with a poor build are able to move to the utmost of their abilities. Unfortunately, on top of whatever disadvantages our children may have been born with, they use their abilities poorly. We should spare our children this unfavorable course in their motor development. What can we do?

Should we exercise the small child? Should we teach the child correct movement? What measures could we take to get good results?

We don’t need to take any special measures.

The question is not how we can “teach” an infant to move well and correctly, using cleverly though up, artificially constructed, complicated measures, using exercises and gymnastics. It is simply a matter of offering an infant the opportunity – or, more precisely, not to deprive him of this opportunity – to move according to his inherent ability.

In the following I want to outline for you the natural course of an infant’s motor development. We are talking about the first two years of the life of a child, for this is when the basic elements of movement are learned. In this period of time the newborn, who can’t do anything but wave her arms and legs around, develops into a child who moves with intent, is able to grasp, stand, sit, and walk.

How does this happen?

The child is born – lies on the back

A newborn infant lies on his back, with bent arms and legs, with closed fists, generally with the trunk and spine slightly bent to one side, the head turned a little sideward. The body, the way the infant is laying, is a little asymmetrical.

Often the two sides are not equally developed; one is a bit longer, the other a bit shorter. As a rule, the newborn always turns the head to the same side.

During the first quarter of the first year, the baby moves the arms and legs more and more while lying on the back. Movements are still abrupt and jerky, all the limbs seem to take part in all the movements at the same time an in the same way. These movements are accidental, without any purpose as yet; they simply accompany a good mood, or crying.

Turning the head

The type of movement changes when an infant begins to follow an object of interest with her eyes and by turning her head. This is when she turns her head in a direction not previously practiced. The chaotic, hasty movements of the hands also change as soon as she begins to pay attention to the movement of the hands with her eyes. She observes her hands; we could even say she takes possession of them with her eyes. She discovers that these are her own hands. Under the constant guidance of her eyes she learns to move her hands with coordination and purpose.

Practices movements of the hands

During the second quarter of the first year, the infant observes his hands with increasing interest, trying out and repeating individual movements. For instance, the infant may make a fist and then carefully open it again – or take hold of one hand with the other. This can go on every day for long hours, for weeks or even months. If something touches the palms of the insides of the fingers, the infant will immediately grasp that object. Letting go is more difficult. That has to be learned separately. The infant often strives for weeks until he has mastered the movement of letting go easily and reliably.

As a rule, an infant’s interest in all the possibilities of moving the hands and fingers is inexhaustible. Later she will play in a similar way with her feet and toes, but never as long and as persistently as with hands and fingers. She grasps her foot with her hand, pulls the foot to her, sucks the toes. Is it possible to grasp something with the toes? Sooner or later most infants try that out, too.

Turns on the side

When the infant is able to grasp well, he not only takes what happens to come into his hands, but stretches his arms more and more toward whatever interests him. Getting closer and closer to reaching the bedrails, he will gradually get pulled over onto his side. He can, however, also get over onto his side by turning the pelvis.

At first lying on his side is a big undertaking. Balance is insecure. We can see that, in the beginning, it is an effort for the infant to stay in that position; it is difficult. She is a bit stiff, supporting herself with her head, shoulder, arm, hand and feet. She returns often to lying on the back in order to rest. Later, after much practice, the child plays easily lying on her side. In this position, in contrast to lying on her back, she has a completely new and different view of things – including her hands. For weeks she plays, lying on her side.

Turning on the belly

As soon as an infant is secure while laying on the side and playing – so secure that he no longer has to pay attention to balance – he may just loose that balance, fall over and land on the belly. Getting over onto the belly can also happen if the momentum of turning onto the side takes him too far, bringing him over onto the stomach. Usually an arm will get stuck under the trunk. That is, of course, unpleasant. The infant often starts crying. We want to help; we turn him over onto the back – and, a few minutes later, find him on the belly again. We can help in the beginning, but we do not turn the infant over again each time – not even if he cries a little. If we know for sure that he did not get onto the belly accidentally, it is better to let him find his own solution. Sooner or later, he will help himself. How? – that depends on the character, on the constitution of the infant. One may pull her arm out, or turn herself back, or fall asleep lying on her belly, and wait thus for the next meal – etc. There are children who, from the very beginning, don’t cry in this situation, but try out different movements until they succeed in coming to lie on their back again. This goes on for many days, repeatedly turning onto their belly and over again to the back. However, the arm always winds up lying under the trunk. Another child may, on the first try, turn a little bit further bringing the weight of the body all the way over to the other side, easily pulling out the arm, etc.

Turns back

Turning over again, ie, from front to back, is easy for newborns. For instance if, for a moment, you lay the naked baby on his belly before a bath, he will often lay his head onto one side, the whole trunk following, and he winds up lying on his back. Later on, however, when he is already able to turn himself over onto the belly and lift his head, we notice that turning back again is not so easy any more. He will learn, however in a few days or weeks.

Spending days lying on the belly

The infant turns onto the back more and more often, and spends more and more time there. Lying on the belly is, however, something that must be learned, practiced and perfected over a long time. At first an infant only lifts her head, then learns how to use her hands and arms while lying on the belly. From the beginning the feet tend to dangle freely in the air, but the trunk remains cumbersome and heavy in movement over a long period. The strong, mobile, flexible trunk – which takes part in all movements of an infant, which moves together with the head and limbs often even guiding a movement – is only the result of months of practice.

Stretching

Now the infant is able to move with intent. As surprising as it may seem, an infant, lying on the belly or on the back, seemingly unable to move anywhere at all, sooner or later will get near to the object or the playpen rails he is trying to reach.

If the child is dressed, usually you will be unable to figure out how he did it. Only by observing the movement of a naked infant’s body can you see what is actually happening. A child bends, stretches herself, makes minimal movements like a caterpillar. This slow and gradual stretching and reaching is one of the most important stages in the motor development of the infant. It goes on for months. During this time the asymmetry of the trunk with which the child is born disappears. Through these natural movements the spine becomes straight; the trunk becomes elastic, flexible and muscular.

I cannot emphasize how important this stage of development is. One proof is that the movements described above are systematically performed as special physical-therapy exercises with children who suffer from distortions of the spine. If infants were not forced to perform other kinds of movements (e.g. to sit up or stand up), and if sufficient space and time were given the children to move, then, day after day for many months, they would stretch themselves, tossing and turning, from the back onto the belly, from the belly onto the back.

Rolling

During the third quarter of the first year the infant is learning how to roll, from the back onto the bely and then from the belly onto the back – rolling on and on in one direction, moving safely and quickly from one place to another, reaching an object that caught his interest. Soon he will be able to roll well enough to get directly where he wants to go. At this time, an infant spends most of the day on her belly. With amazing skill she finds a posture which allows completely free movement of head, neck, arms and legs. Sometimes the trunk is supported only on one point. She is kicking, slowly stretching, rolling – all day long, as she plays.

Creeping on the belly and on all fours

During the fourth quarter of the first year, the infant starts to creep on his belly. At first he usually slides backwards instead of forward. Then he becomes more an more successful in moving forward. Sometimes the arms are more important in the action, sometimes the legs. Many children move forward using the arm-and leg motions of swimming, as if they were doing the crawl-stroke. Sometimes they move so fast and skillfully that we adults could not keep pace with them if we wanted to move forward with the same motions. Each child creeps differently on the belly. It is not by chance that a child chooses a certain form, nor how long she practices different variations of a certain way of moving to get somewhere. As soon as she becomes strong though practice, she lifts herself up on her hands and knees, and swings herself into a hand-knee position. Later she begins to crawl on her hands and knees and, still later, eventually to walking on all fours, on the balls of her feet, like a bear. All this takes several months, during which time the child practices countless variation of these movements.

Children with weaker trunk-muscles move forward with their belly on the ground for a longer time. This strengthens the back and muscles of the trunk. Only after this do they crawl on all fours with the trunk lifted away from the ground. A child with a weak back will crawl on the belly for a long time – later, perhaps for months, on all fours at the “pace of an express train” – without ever considering sitting or standing up. This often happens in families where the parents have had difficulties with their backs. In time, these children too, sit and stand up on their own, without our having sat or stood them up; it just happens later than average. They also learn to stand – to sit and stand correctly – although it may come later than with other children. If we are patient enough to wait for it to happen and if we do not urge them, they, too, will sit and stand straight.

It is clear that a child needs space to be able to crawl, more than there is in a little crib or a little play-pen. Children will only develop as described above if they are given the opportunity to try out these movements when they want to.

Getting up into the vertical

The first attempts to stand up usually take place during the last quarter of the child’s first year. The child never sits or stands up from the position of lying on his back. The sequence is always as I have described it. First he turns onto the belly. Then he begins to pull his knees in, etc. Normally, development from independently turning onto the belly to the beginnings of getting up takes five to six months. Starting in a secure prone position (on the stomach), he turns half onto the side, supported by one arm, and with the head lifted. In this way he comes to a half-sitting position. Later on he will sit up completely. Or he gets up onto his knees, then uses the sole of one foot for support, and then stands up. However, every movement in this process demands weeks or months of practice, like all the other sequences described.

Sitting

One could write long articles on sitting, on different ways of sitting up, on correct and incorrect sitting. What in fact is the difference between “good” and “bad” sitting?

A child who sits well is able to move while sitting. She shifts her weight onto her sitting bones, her trunk rising up almost vertically on this basis. When she sits still, the area of the sacrum (lower back) is straight. The head is line with, and a direct continuation of the back. That is the only way to sit without tiring. This, however, does not mean that a child is always obliged to sit with the trunk vertical; that is only the characteristic, basic position. While playing, the child turns himself to the right and to the left, and bends forward and backward. One can still recognize a child who is sitting well by the appropriate manner in which his trunk bends in the desired direction; no bending takes place which does not originate in the movement or which would hinder the movement.

We are all acquainted with bad sitting. The entire trunk collapses into itself, the spine is bent, belly and chest are compressed, consequently the inner organs as well, and breathing comes difficult. It is typical for us to be afraid that the child could suddenly fall over. Instead of putting her weight over her sitting bones – the parts of the pelvis meant for sitting – she sits behind them on the sacrum. In order to prevent herself from falling backward, she has to bend the whole upper part of her body very far forward.

To sum up: Someone who sits well, who is able to sit, not only sits upright, but also economically. Sitting does not tire this person; it is not a strain for him, but is more likely to be restful. Inappropriate, faulty, unhealthy sitting, however, demands a great effort and is exhausting. When children first sit up, they are not yet “able” to sit. They frequently sit with bent, crooked backs, holding on tight and making a great effort. They tire rapidly and lie down to rest. We never force a child to sit. For some time they continue to play on all fours, or while lying on their front or back – if they are given the opportunity to do so. Later on they will sit while playing, more often and for longer periods of time. But they move about, changing their position, constantly searching for a state of balance. They spread their legs out front and out back, they kneel, sit on their heels, squat on one or both feet, or sit on the ground in between their knees, etc. They try out the various kinds of positions in sitting, just as they have done in the other stages of their movement development. And when they have found a good state of balance and have mastered sitting, they will play in the sitting position – their backs straight – without overexerting themselves or getting exhausted.

Standing up

Usually the child tries standing at the same time as sitting. It can happen that children stand up first, not sitting until later. In a kneeling position or rocking on the knees, they grasp the bars of their playpen or some other stable object and pull themselves up. At first they hardly rest on their feet, although they are standing. Clinging to something with their hands, they hold themselves up in a vertical position. To help support themselves, they may lean on something with their belly, pushing their lower back forward. At this moment many children experience their inability to get back down to the floor. If they get tired, they either let go of what they are holding and fall, or they hold on even tighter, eventually starting to cry. Sometimes we help, but not all the time. The child can and will manage alone. Nothing serious can happen to her if she falls, even if she knocks her head a little. There are also children who are able to sit down again easily the very first time.

When they start to stand up, children put little weight on their feet. They often stand on tiptoe, with their legs spread far apart. They don’t stay in this position for long if there is an opportunity to crawl. They crawl off, stand up again somewhere else, crawl back again etc. Gradually they stand more securely; they rest more of their weight on their feet and they use furniture less in standing up. The knees, which were stiff at first, begin to become elastic. Then the children straighten up; their lower back is no longer pushed forward. They don’t cramp their hands anymore in holding onto something. The trunk as a whole can move more, is more supple. In this phase, they can easily sit down very fast, of bend over and get up again. Soon they can even stand up when there is nothing to get a hold of, only something to touch – as, for instance, when they are next to a wall. For a second as they play, and without noticing it, they are even able to let go of their support. As soon as they stand up, they practice “walking” beside a railing while holding onto it. But I must again emphasize that in the beginning they rest more on their hands and their belly than on their feet.

Standing up alone – without holding on

For months children practice standing up before they can get up without holding onto any thing. As they practice, they look like four-legged animals trying to stand up on their hind legs. They are very insecure at first, falling on their hands again and again until they succeed – for a few moments – in triumphantly remaining standing on both legs without holding onto anything. After a time, they stand up with a toy in their hands, and play in standing – more and more often without even noticing it. This is standing, and only in this moment when they are able to stand are they ready to start walking. Now the children begin walking “freely” – “taking off” on their own. It usually takes four to six months for a child to learn to stand up, then to stand without holding on and finally to walk on his own. They need this time in order to become able to transfer the weight of their body to their footsoles, with stability. Standing up without a support and walking alone take place in succession. All the time in between, if they aren’t trying to stand, the children play, lying on the belly, sitting or crawling.

Walking about on their own

In general, a child starts walking freely during the first half of the second year, if no one has interfered with her motor development. However, this is still more a matter of experimenting. Not until later will the child use walking instead of crawling for the purpose of moving from one place to another. A child who can already walk well will, for a long time, play mainly while squatting, kneeling or crawling. Many years later, children still like to kneel and squat when playing. To be sure, I must once again add: if we do not forbid them to do this.

During the first phase of walking freely, children as a rule move with legs spread far apart and their feet turned far inward – insecure, like a sailor on a rocking boat – holding their arms like a tight-rope walker. They keep their balance with their hand, and try to clutch the ground with their feet, talking small steps, often lifting their knees up high. That lasts only a few days. Soon the necessary assurance has been reached. It seems that they walk with more ease, although the legs remain spread apart and the feet turned inward for many months, even for years. If their feet, knees and hips are weak and poorly built, the children continue walking this way for longer.

This, too, will correct itself if we are patient enough to wait. We do not interfere in the way the child moves, but continue to provide him at all times with the opportunity to move and play however he likes! We don’t do anything to “straighten out” his legs or his gait. We let him walk with widespread legs as long as he is insecure, and with inward-turned feet as long as the soles of his feet are not yet strong! We allow a child to roll and crawl, even with she can already walk! We do not demand that she walk long distances!

For many more years a child whose legs are weak will tire easily, and move with a peculiar foot position. However, if we don’t overstrain or make too great demands on the child, then the legs will become stronger and, without anyone making corrections or interfering, the feet will adjust their position to be more toward the front. The legs come closer together, the walking becomes beautiful and secure, the child as a whole has more endurance.

Early development, as far as a time schedule is concerned, is not the same for all children. In general, the time differences for learning certain movements are very great, especially for those infants whose development no one wanted to force. Which movements an infant will practice, and when, depends not only on the state of health and upbringing, but also on many other factors: on mental and bodily predispositions; on eventual anomalies; on the strength of the joints; on the level of development of his or her sense of balance; etc. One child already crawls between 7-8 months, stands up shortly after that, and sits up. Another, although otherwise completely well developed and healthy, may start crawling at the same time or a little later, but does not stand up or sit up until one year old. If provided with sufficient space and not put into a passive sitting or standing position, these positions may not occur to this child. They will come later.

The most important thing has not yet been mentioned: namely that an infant’s own movements, the development of these movements and every detail of this development are a constant source of joy to him.

If one does not interfere, an infant will learn to turn, roll, creep on the belly, go on all fours, stand, sit, and walk with no trouble. This will not happen under pressure, but out of her own initiative – independently, with joy, and pride in her achievement – even though she may sometimes get angry, and cry impatiently.

At the same time, such an infant is following his own movements with extraordinary interest and amazing patience. He attentively studies one movement innumerable times. He enjoys and becomes absorbed in each little detail, each nuance of a movement, quietly taking his time in an experimenting mode. Perhaps it is the very repetitiveness of this study which brings such delight to a child. During the first two years, she is busy – or better, she is “playing” – with each movement for days, weeks, sometimes months. Each movement has its own history of development. Each one is based upon the other. Carefully and cautiously she makes progress. She has time. She gets to the root of things and likes to be completely sure of something. This is the way a child learns to sit and stand well – generally speaking, to move well altogether.

What is most important, however, is not the result, but the way to it. This learning process will play a major role in the whole later life of the human being. Through this kind of development, the infant learns his ability to do something independently, through patient and persistent effort.

While learning during motor development to turn on the belly, to roll, creep, sit, stand and walk, he is not only learning those movements, but also how to learn. He learns to do something on his own, to be interested to try out, to experiment. He learns to overcome difficulties. He comes to know the joy and satisfaction which is derived from this success, the result of his patience and persistence.

|

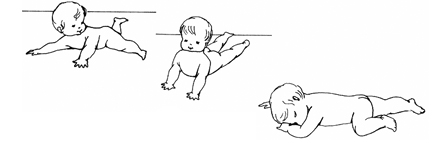

Illustrations by Klara Pap.

|